History

Asprey’s ‘Great Exhibition of 1851’ Dressing Case

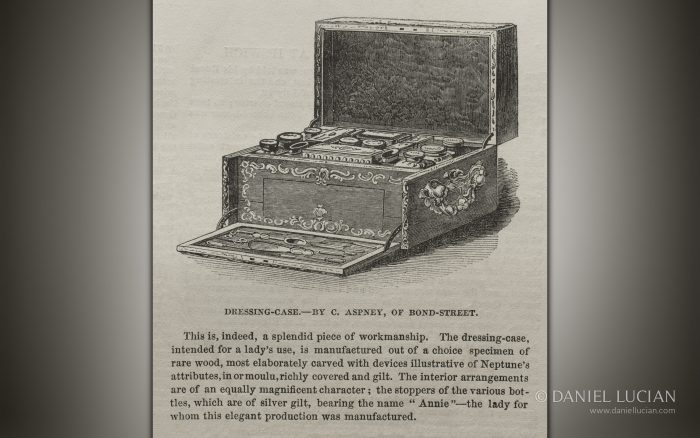

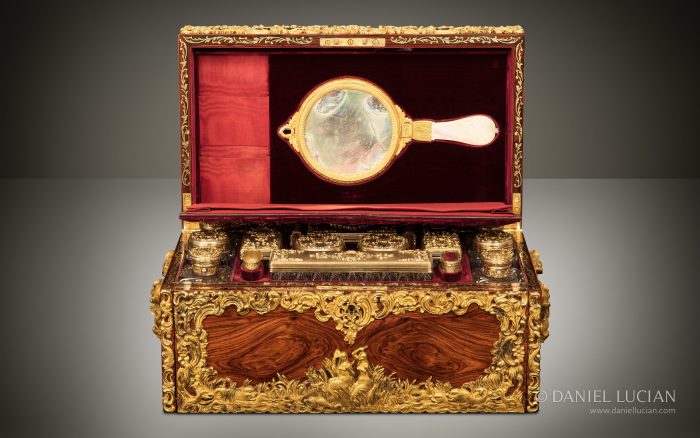

On public view for the first time since 1851, this magnificent dressing case was chosen by both Charles Asprey (I) and (II) to be displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, London.

This large antique dressing case is veneered in Kingwood, retaining its original vibrant colour and finish. There are applied ormolu panels to the lid and front fascia of the case that depict Neptune and other mythical sea creatures. The two large ormolu side handles are in the design of fish, elaborately entwined. The centre piece to the lid bears the name ‘Annie’, belonging to Annie Gambart, the 16 year old wife of the famous Victorian art dealer, Ernest Gambart.

The interior of the dressing case is lined and ruched with its original claret red velvet. The interior rims are inlaid with a delicate brass foliate design accompanying the gilt engraved hinges and lock. The main compartment holds 13 heavy gauge silver-gilt topped, cut glass bottles and jars; these include four spring-loaded perfume bottles, two powder jars, two toothbrush jars, a soap jar, two lotion jars, a spring-loaded travelling inkwell, and a spring-loaded jar for liquids and creams. Additionally fitted are a silver-gilt perfume bottle funnel, pin cushion, match vesta/striker and nib blotter both in the form of bound books. All the interior pieces bear the matching ‘Annie’ cipher. The silver was manufactured by Thomas Diller and hallmarked London, 1848. The interior facing of the perfume bottles are engraved with, ‘Asprey – 166 Bond St’.

Silver-gilt bottles, jars and accessories with an overlaid foliate design and decorative ‘Annie’ cipher.

Close-up view of the overlaid foliate design and decorative ‘Annie’ cipher taken from a silver-gilt lidded jar.

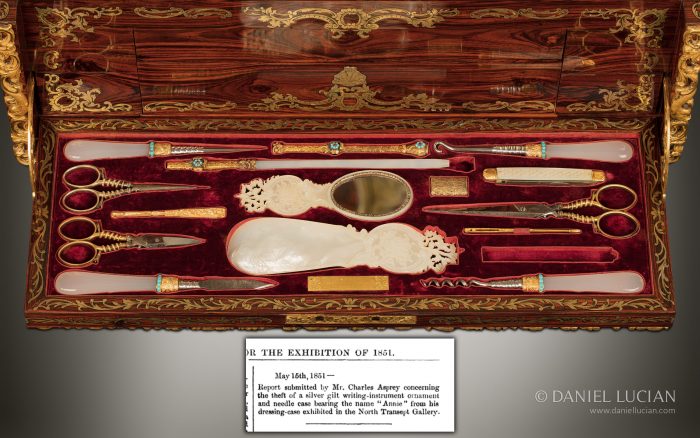

The front panel of the dressing case drops forward to reveal a fitted tool tray to the reverse, as well as a brass plaque engraved with, ‘Asprey – Manufacturer – 166 Bond Street’. The set consists of a stiletto tool, button hook, corkscrew and nail file with handles of White Cornelian, mounted with gold and inset with turquoises, three pairs of gilt handled scissors with a design of entwined sea serpents around the handle shank, a gilt engraved retractable pencil and White Cornelian pen with a matching ‘Forget-Me-Not’ design of inset turquoises surrounding a ruby, a mother of pearl scaled penknife, a gilt engraved pencil lead case, a gilt engraved pair of tweezers, a gilt engraved ribbon threader, a fretworked mother of pearl shoe horn and matching miniature hand mirror bearing the ‘Annie’ cipher.

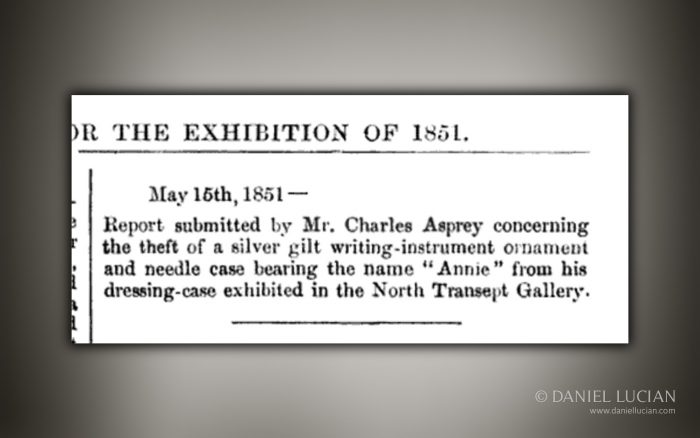

You will notice two small gaps in the tool tray; one would have been for the needle case, and the other would have been for the finial to the White Cornelian pen. Now why are these pieces missing? Taken from what seems to be a criminal activity report from the Great Exhibition, we read the following, ‘May 15th 1851 – Report submitted by Mr Charles Asprey concerning the theft of a silver gilt writing-instrument ornament and needle case bearing the name “Annie” from his dressing-case exhibited in the North Transept Gallery’.

Crime report submitted by Charles Asprey two weeks into the Great Exhibition.

Three pairs of gilt handled scissors with a design of entwined sea serpents around the handle shank.

A gilt engraved retractable pencil, pencil lead case, and white cornelian pen with a matching ‘forget-me-not’ design of inset turquoises surrounding a ruby.

A fretworked mother of pearl shoe horn and matching miniature hand mirror bearing the ‘Annie’ cipher.

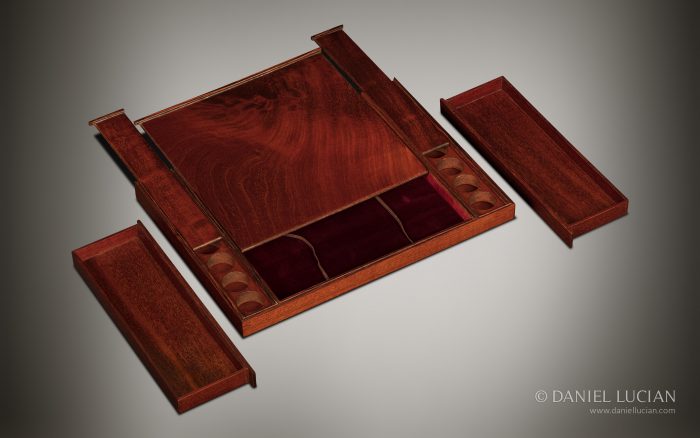

The front fascia of the interior is inlaid with ornate engraved brass; a central cockle shell motif is hinged to act as a handle for the lower drawer. This lower drawer contains four ivory brushes, for hair and clothing, that have been carved with the matching ‘Annie’ cipher. Two smaller spring-loaded drawers, on either side of the lower drawer, are deployed by floor mechanisms beneath the rear left and right bottles in the main compartment. The spring-loaded upper drawer, lidded and velvet-lined for jewellery, can be released by pressing down on the middle screw from the engraved gilt brass plate to the rear rim of the dressing case.

View of the four deployed concealed drawers, three of which being spring-loaded. A central cockle shell motif is hinged to act as a handle to manually pull out the lower middle drawer.

Close-up view of the four deployed concealed drawers, three of which being spring-loaded. A central cockle shell motif is hinged to act as a handle to manually pull out the lower middle drawer.

The lower drawer contains four ivory brushes, two for hair and two for clothing. The two middle brushes are fitted ‘head to toe’.

With the lower drawer removed, a concealed spring-loaded floor unit is accessible. This floor unit, made from solid Mahogany, is removed by pushing it backwards slightly, thus unlatching it and allowing it to pop up; it contains three slide-covered sections, two of which contain gold sovereign holders. With this concealed floor unit removed, two side mounted Mahogany spring-loaded drawers can be released from the very base of the dressing case.

Mahogany concealed floor unit containing three slide-covered sections, two of which containing gold sovereign holders. The two mahogany spring-loaded secret drawers are side mounted in the base of the box, only becoming accessible when the concealed floor unit is removed.

The ruched velvet panel in the lid can be released forward to reveal a secret letter wallet on the reverse, as a well as a sculpted mother of pearl handled face mirror fitted to the underside of the lid. The embossed, gold tooled mark onto leather reads, ‘Asprey – Manufacturer – 166 Bond Street’.

The dressing case is fitted with a Chubb Detector lock. This lock was designed to be impossible to pick or open without its dedicated key, whilst also having the ability to alert its owner to any unauthorised access attempts. The impressive gilt-brass key has been sculpted to portray the face of Neptune.

History and Provenance:

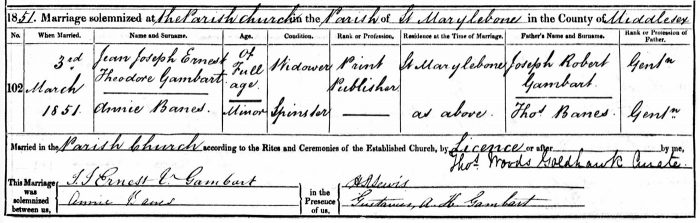

Being one of the first major dressing cases to begin its manufacture at Asprey’s then new 166 Bond Street address in 1848, the project was only finally completed in early 1851. It was purchased by Ernest Gambart (1814-1902) in 1851 as a wedding gift for his 16 year old wife, Annie Gambart (née Baines) (1835-1870).

Ernest Gambart was a very important, influential and indeed successful art publisher and dealer, responsible for transforming London’s art world. He created a platform to promote and sell art work on an international scale, introducing some of the finest foreign art work to the United Kingdom through regular exhibitions as well as from his own galleries. He worked with some of the most respected British and European artists of the time, to include Joseph Mallord William Turner, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Rosa Bonheur, Lawrence Alma-Tadema and William Powell Frith.

It was well documented that when Ernest first met Annie, he instantly became besotted with her, lavishing her with the finest jewellery, clothing and luxury items. They were married on the 3rd March 1851 at St Marylebone Parish Church, London. Shortly after this, the dressing case was loaned back to Asprey to be presented at the Great Exhibition.

Ernest and Annie Gambart’s marriage certificate from the 3rd March 1851.

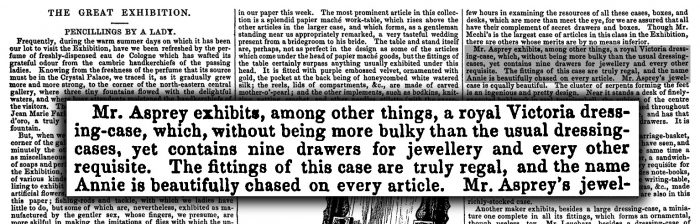

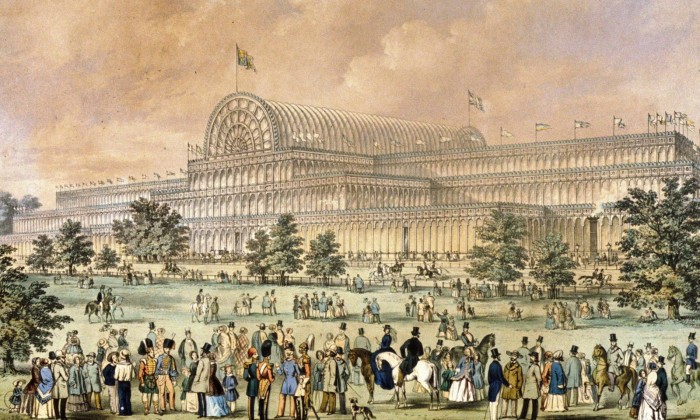

The Great Exhibition is considered to this day to be one of the most, if not the most important world exhibition of all time. Organised by Henry Cole and Prince Albert, it displayed and celebrated contemporary industrial technology, craftsmanship, art and design from over 15,000 national and international exhibitors. The venue, named ‘The Crystal Palace’, was an impressive 564 metre long, 138 metre wide cast iron and plate glass structure taking up 19 acres of London’s Hyde Park.

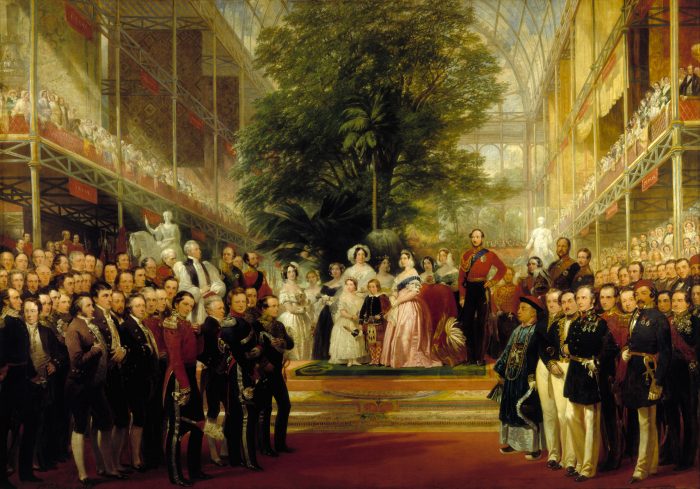

The exhibition was opened on the 1st May 1851 by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and ran for just over six months, before closing on the 11th October 1851. During this period, about six million people attended, making the exhibition a resounding success, whilst also creating a considerable profit; the proceeds of which helped to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum, Natural History Museum, Royal Albert Hall, Imperial College, Royal College of Art, and the Royal College of Music.

Asprey received an ‘Honourable Mention’ for this dressing case by the board of judges at the Great Exhibition. Having only been in business in their own right for just over three years, this result immediately gained Asprey great admiration and recognition for the quality of their work, thus concreting the Asprey name to be synonymous with the utmost luxury and exclusivity to this very day.

It is believed that this box made its way back into Asprey’s own archives, held at 166 Bond Street, around 1867. This ties in with the year that Ernest split up from Annie, but also the year that Ernest moved his art gallery to the rear of Asprey’s shop located at 22 Albermarle Street; 166 Bond Street backed directly onto 22 Albermarle Street and, in 1861 Charles Asprey (II) purchased number 22, in order to join them and have shop fronts on two of London’s most exclusive streets.

Seemingly the dressing case remained in Asprey’s archives until the late 1960’s, where it was then purchased through the Asprey shop by a Canadian businessman as a wedding anniversary gift for his wife.

This exact dressing case features in the following publications:

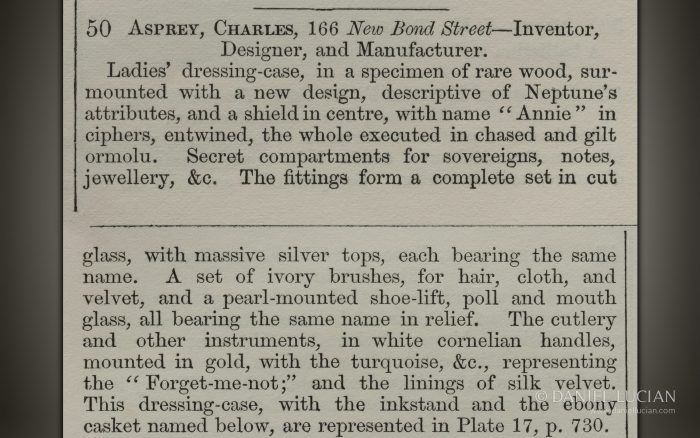

‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’- Part III, Classes XI to XXX Manufacturers And Fine Arts. (Spicer Brothers, 1851). An Illustration and full description – (Plate 17, Page 791 & 793).

‘The Crystal Palace, And Its Contents; Being An Illustrated Cyclopaedia Of The Great Exhibition Of The Industry Of All Nations, 1851’. (W. M Clark, 1852). An illustration – (Page 284).

‘…For The Exhibition Of 1851’, May 15th 1851 (unknown title, page and publisher). A descriptive crime report from the Great Exhibition.

‘Illustrated London News’, May 3rd 1851. An Illustration – (Page 363).

‘The Lady’s Newspaper’, September 6th 1851. A Description – (Page 134).

‘Illustrated London News’, September 20th 1851. An Illustration and full description – (Page 381).

‘Directory of Gold and Silversmiths, Jewellers, and Allied Traders, 1838-1914’ by John Culme (ACC Art Books, 1987). Full description – (Page 17).

‘Asprey 1781-1981’ by Bevis Hillier (Quartet Books Ltd, 1981). Illustrations and full description – (Page 31, 32 & 33).

An illustration of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

A description of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

An illustration and description of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Illustrated London News’, September 20th 1851.

An illustration of the Asprey dressing case taken from the book, ‘The Crystal Palace, And Its Contents; Being An Illustrated Cyclopaedia Of The Great Exhibition Of The Industry Of All Nations, 1851’.

A description of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘The Lady’s Newspaper’, September 6th 1851.

The Great Exhibition of 1851

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, or simply the Great Exhibition, was created and organised by Henry Cole with the backing of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and its president, Prince Albert.

The exhibition displayed and celebrated contemporary industrial technology, craftsmanship, art and design from over 15,000 national and international exhibitors. There was however an ulterior motive for setting up this exhibition; to promote and highlight to the world Great Britain’s position at the forefront of industry.

The venue, designed by Joseph Paxton, and named ‘The Crystal Palace’, was an impressive 564 metre long, 138 metre wide cast iron and plate glass structure taking up 19 acres of London’s Hyde Park.

The exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert on the 1st May 1851 and ran for just over six months. Indeed, Queen Victoria herself attended the exhibition on 33 different occasions. By the time of its closing on the 11th October 1851, the exhibition had welcomed over six million attendees. It was a resounding success and created a considerable profit of over £186,000 (approximately £24.5 million in today’s money); the proceeds of which, purchased 87 acres of land in London’s South Kensington, and helped to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum, Natural History Museum, Royal Albert Hall, Imperial College, Royal College of Art, and the Royal College of Music

Renowned manufacturers, notably Asprey, Aucoc, Edwards, Leuchars and Mechi, exhibited their finest dressing cases. Prize medals for excellence of workmanship were awarded to Aucoc, Audot, Edwards, Laurent and Leuchars, with Asprey, Austin and Strudwick receiving honourable mentions.

‘The Crystal Palace’, venue of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, London.

Interior view of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

‘The Opening of the Great Exhibition by Queen Victoria 1 May 1851’ by Henry Courtenay Selous.

Refreshment area at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

An illustration of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

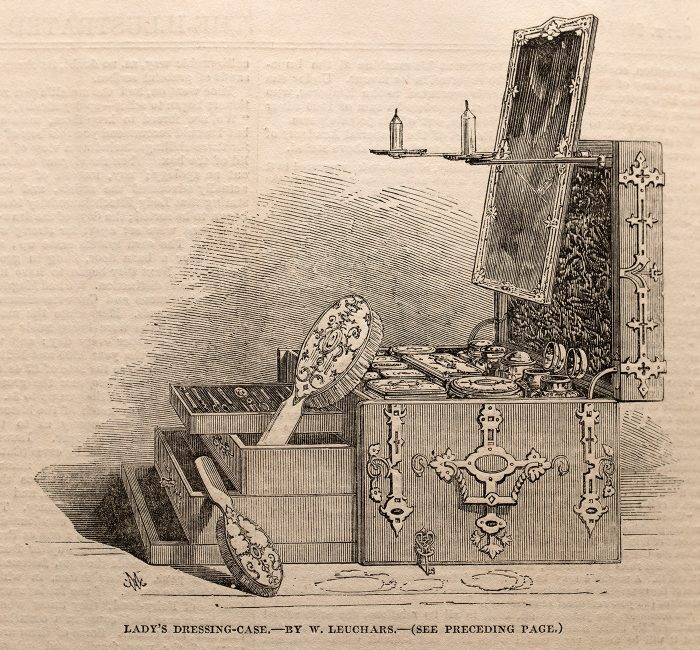

Lady’s dressing case by William Leuchars taken from the September 1851 edition of the Illustrated London News.

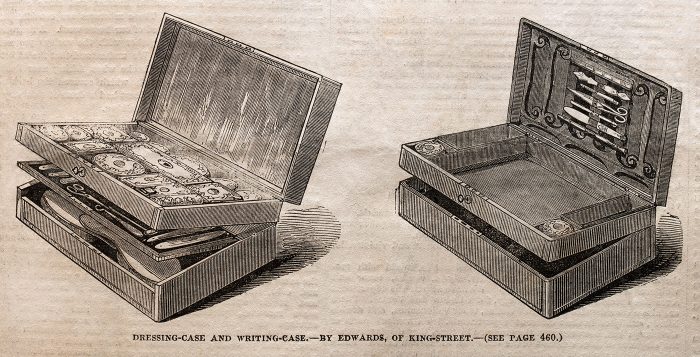

Gentleman’s dressing case and writing case by Edwards, entered into the 1851 Great Exhibition.

The International Exhibition of 1862

The International Exhibition of 1862, otherwise known as the Great London Exposition, showcased contemporary industrial technology, craftsmanship, art and design from 36 countries from around the world. It was organised by the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, and financed from the proceeds of the Great Exhibition of 1851 by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition 1851. READ MORE

History of the French Nécessaire de Voyage

The origins of the French travelling box date back to the late 14th century, with some of the earliest examples containing the most basic equipment for personal grooming. Over the centuries these boxes, most often the property of royalty, nobleman and other wealthy individuals, evolved from purely useful travel accessories into decorative and valuable luxury accessories. With these boxes gaining popularity, variations for toiletries, eating and drinking, sewing, writing, and other scientific purposes were manufactured. READ MORE

Eras and Periods

Regency Period (1811 – 1820)

The Regency period began in 1811, when King George III was deemed unfit to rule Britain, and his son George, the Prince of Wales, took over as Prince Regent. It wasn’t until King George III died in 1820 that the Regency period ended. READ MORE

History of Dressing Cases

Towards the end of the 18th century, dressing cases were manufactured specifically to accompany upper class gentleman during travel. Dressing cases were originally rather utilitarian but they spoke volumes about their owners’ wealth and place in society, as at that time, travelling was only undertaken by the elite. READ MORE

Price On Application

Price On Application