F. L Hausburg

Friedrich Ludwig Hausburg was born in Berlin, Prussia in 1817. He began his career working alongside his uncle, August Wilhelm Bernhardt Promoli, based at 4 Rue de Boulogne, Paris, specialising in fine jewellery, clocks and a wealth of other luxury items.

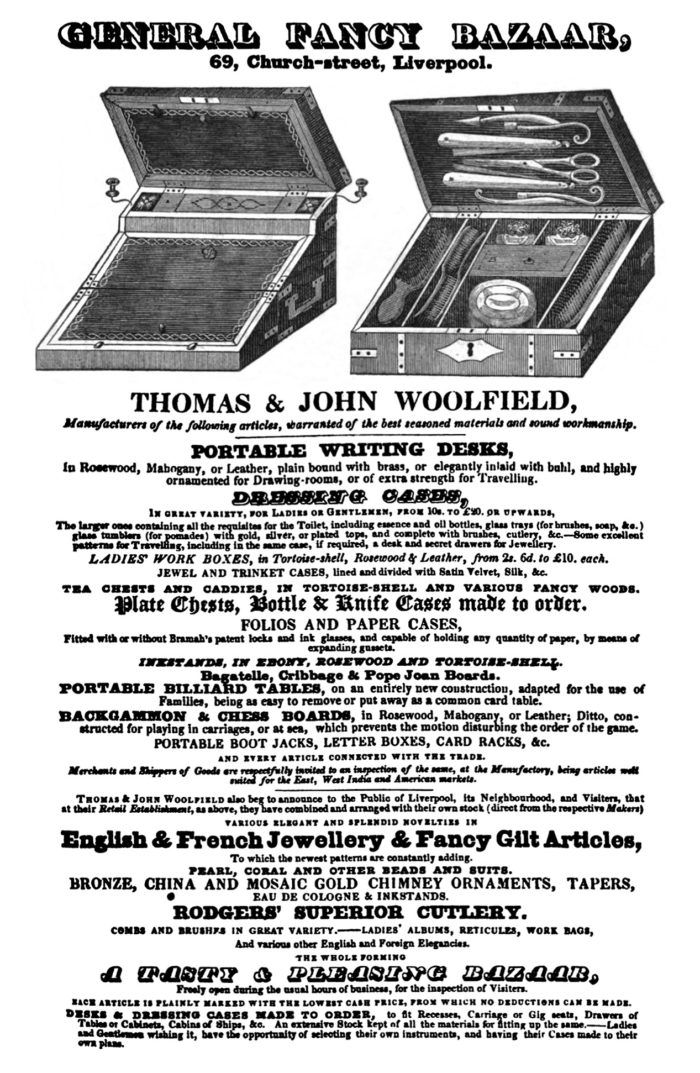

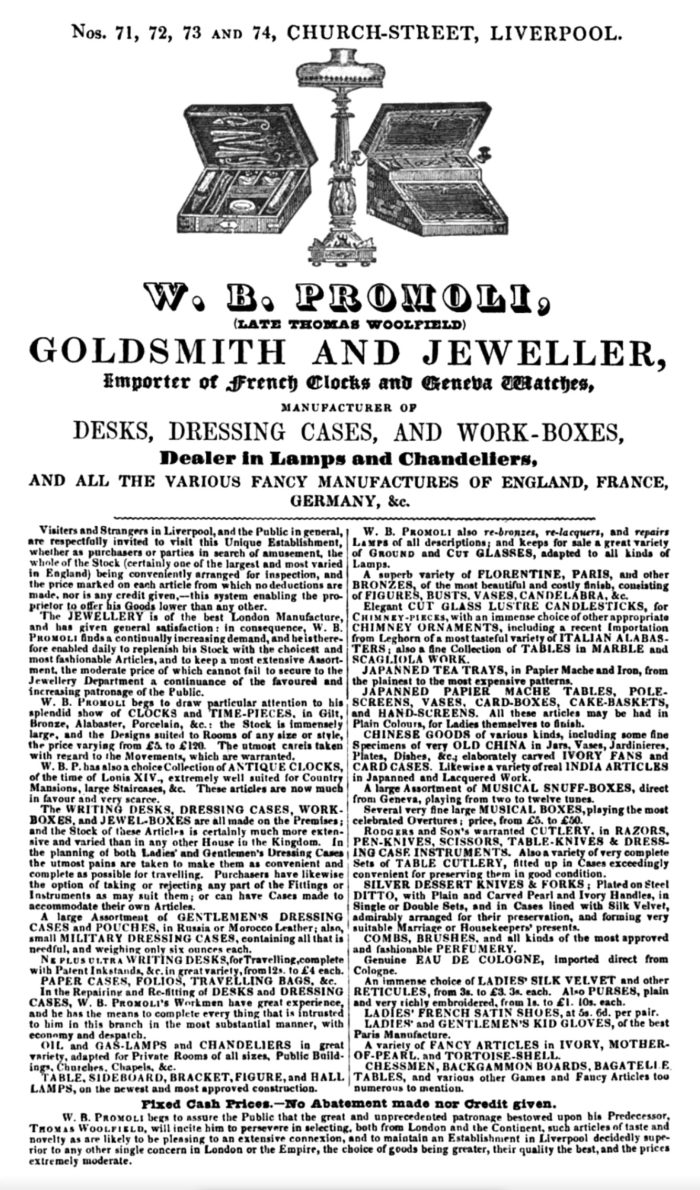

An advertisement from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory confirms that Promoli had taken over the business of Thomas Woolfield by 1837. Woolfield was the uncle, by marriage, of Hausburg’s wife, Catherine Mossop; he was predominantly a writing and dressing case manufacturer, but also retailed a vast array of fancy goods. Having been previously known as Woolfield’s Bazaar, based at 71 & 72 Church Street, Liverpool, the business was now titled as W. B Promoli and had expanded to 71, 72, 73 & 74 Church Street.

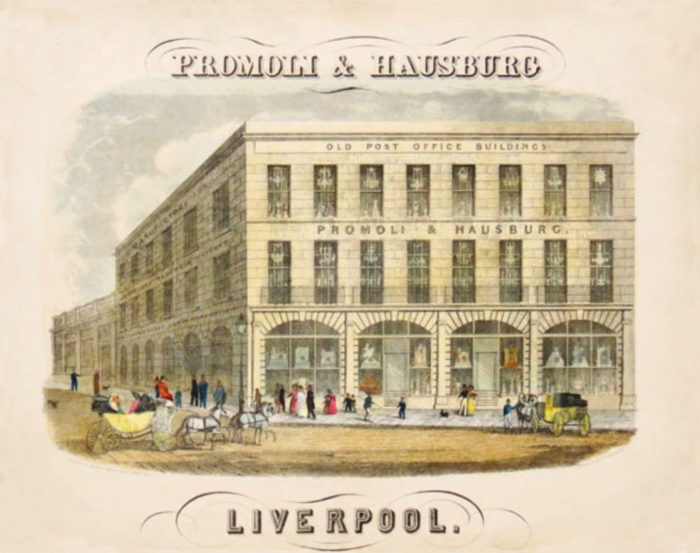

In August 1840, both Hausburg and Promoli were naturalised as British citizens; a legal act that could not only boast having Queen Victoria as its personal signatory but that, uniquely, was passed in just five weeks instead of a usual four years. That same year the name of the business was changed to Promoli & Hausburg, with their address now declared as Old Post Office Buildings, 24 Church Street, Liverpool. Together, they advertised themselves as ‘Jewellers, Watchmakers, Manufacturer’s of Desks, Dressing Cases, Lamps and Chandeliers’.

Just a year later in 1841, the business was solely in the hands of Hausburg who continued dealing in the same vast range of luxurious inventory.

Looking at Hausburg’s work, one can clearly see the French influences harking back from when he was working in Paris; whilst very well versed in the more ‘reserved’ British style of exterior case design, he often produced pieces that featured far more lavish and intricate inlay work. Hausburg was known to use materials such as brass, pewter, ivory, abalone and mother of pearl to inlay into woods, or produce pieces dressed with Boulle work (tortoiseshell inlaid with brass). These decorative influences were often also applied to the interiors of his cases, with the inclusion of elaborately gold tooled leather to line the walls, floors, trays, and other components.

Hausburg retired in 1860 at the age of 43, selling his business to W.H Tooke who continued it from the same address. When Hausburg died in 1886, his estate was valued at a staggering £180,000 (£24 million in today’s money).

There is a wonderful, if not a little manic, article entitled ‘A Fashionable Shop At Liverpool’ written by a New York journalist, taken from the The Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review – June 1849, Vol. XX, No. VI; this journalist is in a state of rapture and trying, or rather struggling, to accurately make sense to his readers [and, I must assume, himself] just exactly what he has experienced after having visited Hausburg’s establishment,

“It must not for a moment be confounded with those receptacles of low-priced and slop-manufactured articles, commonly called bazaars, where there is much glitter and show, much tinsel and gay color, but little solid and substantial value. Presenting infinitely more variety than the best or more extensive of the marts just alluded to, it ranks above them in a degree that will not admit of the slightest comparison in the richness, rarity, beauty, and we may, with propriety, say splendor, of the articles offered for inspection. Indeed, I should not have written the word bazaar in connection with it but for the purpose of preventing any mistake or comparison of ideas in the mind of my readers. It bears about the same relation to a bazaar that a costly jewel, tastefully mounted in fine gold, does to a glittering gewgaw of paste set in Dutch metal. It wants an appropriate designation, for it is so completely unique that no ordinary term will serve to convey to the mind any notion of its extent, appearance, or purposes. I cannot call it a shop or a store without conveying an inappropriate image or false impression.I have seen the magnificent shops of London and Paris, and there are some fine shops, too, in Liverpool, but this establishment is so entirely different from them that the designation would be utterly inappropriate. As to ordinary shops, it is as infinitely superior to them as a palace is to a cottage.“

An Illustration from 1840 of Promoli & Hausburg’s emporium, manufactory and warehouse based at Old Post Office Buildings, 24 Church Street, Liverpool.

F. L Hausburg manufacturer’s mark gold tooled onto leather from an 1852 antique dressing case in burr walnut.

Thomas & John Woolfield advertisement taken from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory, For 1828-9.

W. B Promoli (late Thomas Woolfield) advertisement taken from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory, For 1837.

Price On Application

Price On Application