Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’

If a lock with 12 sliders has a 1 in 479 million chance of being opened without its dedicated key, and then by adding just one more slider raises that probability to 1 in 6.2 billion – how on earth does someone successfully pick a lock with 18 sliders? This is the story about a challenge that had remained unanswered for over 60 years, and the charismatic American that seemingly achieved the impossible. His actions would bring insecurity all the way up to the highest establishments of England. This unusual series of events that took place in 1851 became known as the Great Lock Controversy.

Joseph Bramah set up his locksmithing business at 124 Piccadilly, London in 1784. The technical achievement and level of security offered by Bramah’s locks were considered far beyond anything presented by his peers. As a result, the demand for his locks greatly outweighed his ability to manufacture them. Bramah needed to find a way to produce these locks in larger numbers, make them more economical to manufacture and, improve and standardise their quality. The solution came in 1789, when Bramah hired Henry Maudslay upon the recommendation of his employees. Maudslay was only 18, but his technical and mechanical abilities impressed Bramah to such a degree that he soon became his chief engineer. The collaboration of both Bramah and Maudslay produced a set of precision tools and machinery that addressed all of Bramah’s previous issues.

Joseph Bramah (1748 – 1814).

Henry Maudslay (1771 – 1831) – Chief Engineer at the Bramah Lock Company from 1789 – 1797.

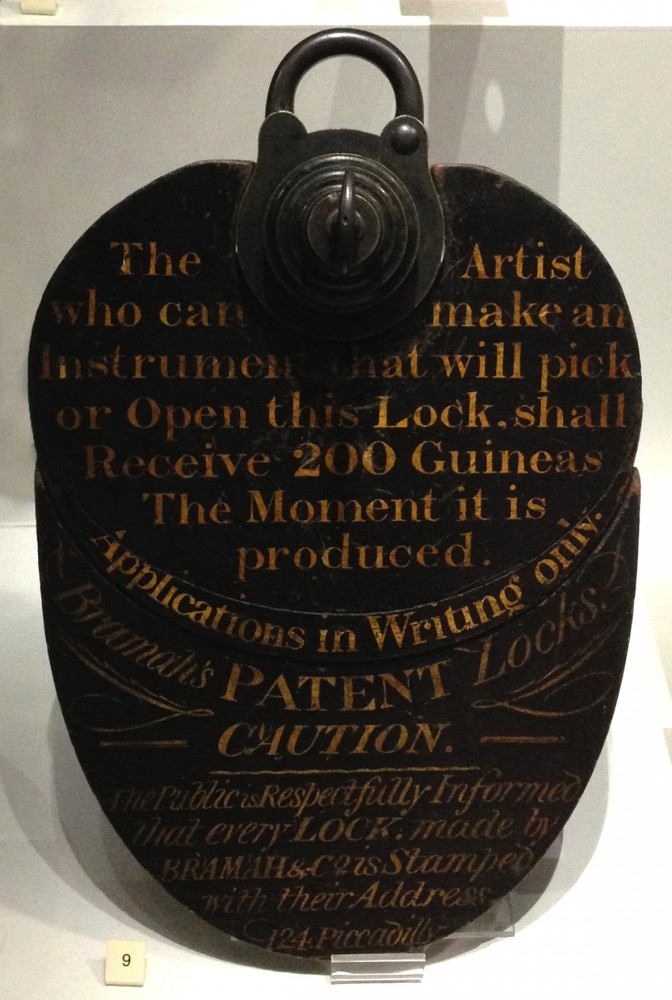

In 1790, Maudslay was instructed to manufacture a padlock so secure and un-pickable that it couldn’t be opened by any means other than with its own dedicated key. With overwhelming confidence, Bramah mounted the padlock, placed it in his shop window and issued a challenge: in gold lettering upon a black background, he stated, ‘The artist who can make an instrument that will pick or open this lock shall receive 200 Guineas [approximately £30,000 in today’s money] the moment it is produced’.

Recreation of Bramah’s shop front at 124 Picadilly, London, with the ‘Challenge Lock’ on display, taken from the Science Museum in London.

Joseph Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ mounted within its challenge board, as displayed in his shop window from 1790. Now displayed at the Science Museum in London.

Joseph Bramah died in 1814, never seeing his challenge overcome, but his son, Timothy, continued the business. [Future mentions of Bramah refer to either Timothy Bramah, Francis and Edward Bramah (his brothers who joined the business during the early 1820’s), or Bramah & Sons as a company]. Despite one failed attempt documented in 1817, Bramah’s Challenge Lock remained as a novel fixture gathering dust in their shop window.

Articles began to surface in the press about the shortcomings of some Bramah’s locks; it was stated that they could be picked by an exhaustive and methodical process of applying differing pressures to the individual sliders, thus freeing the barrel and allowing it to operate the locking bolt. In 1817, one of Bramah’s employees, William Russell, came up with the addition of false notches on all the sliders and the locking plate; this made it seemingly impossible for the lock picker to ascertain the correct pressures and settings to be applied in order to free the barrel. Russell’s false notches were added to all 18 sliders of the Challenge Lock! With most of Bramah’s box locks having between four and six sliders at that time, a lock fitted with 18 was surely impenetrable.

The importance and exclusivity of the Great Exhibition of 1851 attracted countries from all over the world to exhibit the finest examples of their work.

Interior view of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Day & Newell were a New York locksmith company that sent over their sales representative, Alfred Charles Hobbs, to present their ‘Parautoptic’ lock at the Great Exhibition [this lock went on to win a prize medal at the exhibition]. Not only was Hobbs an accomplished locksmith and inventor, he was also a very good salesman and indeed, showman. His thinking was that in order to promote their own lock [or more likely to promote himself], he should highlight the shortcomings and insecurities of those belonging to the competition; these being Jeremiah Chubb’s Detector lock and Joseph Bramah’s Challenge Lock.

Alfred Charles Hobbs (1812 – 1891).

Hobbs contacted the firm of Chubb on the 21st July 1851 announcing that he intended to pick their famed ‘Detector’ lock the very next day; the lock in question was fixed to an iron door of a vault within the Depository of Valuable Papers, in Westminster. Hobbs, as good as his bold words, unlocked Chubb’s Detector lock in only 25 minutes, then taking a further 7 minutes to relock it. Hobbs gained immediate celebrity status in the press, adding further to the pomp and circumstance of the Great Exhibition.

Front view of the internal mechanism of a Chubb ‘Definitive’ Detector lock from 1849.

Capturing the fascination and (somewhat reluctant) support of UK population, there was now only one more hurdle for Hobbs to overcome – Bramah’s Challenge Lock.

Prior to his Chubb Detector lock challenge, Hobbs had contacted Bramah on the 2nd July 1851 informing them of his intention to take on their challenge, and to request permission to make a wax impression of the lock’s keyhole in preparation.

A committee of three were appointed to manage and act as arbitrators for the challenge, with an agreement between Hobbs and Bramah drawn up on the 19th July 1851. It was stated:

- Hobbs had 30 days to open the lock.

- The lock was to be sandwiched between two pieces of wood and affixed to a wall (with sealed screws) in order to limit access to only the keyhole and hasp.

- The key would remain in the sole possession of Bramah at all times.

- The keyhole should be covered by an iron band, to be sealed by Hobbs, each time the lock is left unattended.

- If Hobbs was successful in picking or opening the lock, the key was to be used; if the key worked the lock as expected it would be accepted that the lock had been legitimately picked or opened, rather than by being forced and damaged.

Removing all potential grounds of suspicion associated with the interference of the lock during the challenge period, Bramah decided to relinquish the right to hold onto the key. Instead, Bramah recommended that the key be sealed away until either the culmination of the challenge or the 30 day period.

On the 24th July 1851, the Challenge Lock was removed from Bramah’s shop window and placed in one of the upper rooms where Hobbs, in isolation, began his seemingly impossible undertaking.

Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ and key, manufactured by Henry Maudslay in 1790. Photo courtesy of the Science Museum, London.

Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ and key, manufactured by Henry Maudslay in 1790. Photo courtesy of the Science Museum, London.

After a week having elapsed and with curiosity growing, Bramah wrote to the committee requesting that they attend their establishment in order to inspect Hobb’s progress. A reply to this request was received stating that all three members of the committee were in Paris, and although they would have liked to attend, they were not sure what use their inspection would serve. Upon hearing this, Bramah disallowed Hobbs from continuing his efforts until more clarity could be lent to this situation.

On the 8th August 1851, Bramah wrote to the committee again expressing their disappointment at their lack of attendance, and at not being granted the opportunity to see the result of the key operating the lock; even though Bramah had relinquished their rights to the key’s usage, they were in the belief that this wouldn’t exclude members of the committee doing so on their behalf. Bramah suspected that Hobbs would have likely damaged the lock to such an extent that the key would no longer work.

A meeting took place between Bramah and the committee on the 15th August 1851. Bramah requested that they take the opportunity to test the key in the lock, as well as enlist someone to remain present during the remainder of the challenge. The committee rejected both requests; they didn’t believe there was any value to testing the key until the conclusion of the challenge, or any necessity to have a person present during the process. They thought that if Hobbs did indeed damage the lock in any way, he had the right to repair it accordingly should the time limit allow.

As of the next morning, Hobbs was able to return to his task.

Bramah wrote to the committee on the 19th August 1851 expressing that they felt it would be impossible for their challenge to now be met in a fair and reasonable way so as to be able to offer the reward money; their reasoning being that the privacy afforded to Hobbs during the challenge prevented them from knowing if the lock had been opened and, if so, how the instrument in question was created and used. Bramah received no response to their letter.

On the 23rd August 1851, Hobbs, in the presence of two of the three committee members, displayed the Challenge Lock with its hasp open, then demonstrated its bolt moving back and forth. This seemingly impossible achievement had taken Hobbs over 51 hours of labour spread over 16 days.

On the 29th August 1851, now in the presence of all the committee members and Bramah, Hobbs again displayed the hasp of the Challenge Lock open. Attached to the wood surrounding the lock were several connected pieces of apparatus that kept a rod tightly pressed into its keyhole; the addition of a small, bent, handheld piece of steel enabled Hobbs to turn the barrel of the lock allowing the hasp to re-enter its socket. Hobbs also produced two further tools; one similar to a stiletto, and the other similar to a crochet hook. Bramah immediately requested that the key be tried in order to see if the lock had indeed been successfully picked and not just forced; this request was denied by the committee in order to allow Hobbs a further day to get the lock back into its original state. On the next day, the key was inserted and it operated the lock without issue.

Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ and key with its hasp open.

The committee submitted their full report of the challenge on the 2nd September 1851, concluding:

“We are, therefore, unanimously of the opinion that Messrs. Bramah have given Mr. Hobbs a fair opportunity of trying his skill, and that Mr. Hobbs has fairly picked or opened the lock, and we award that Messrs. Bramah and Co. do pay to Mr. Hobbs the 200 guineas.”

Bramah responded to the committee by letter the very same day; they acknowledged the opening of their lock, yet made reference to their (ignored) letter from the 19th August 1851 echoing their concern regarding the eligibility of the reward money. Bramah believed it was only fair that the use of the key during this period would have reset the sliders and mechanism, therefore simulating normal use of such a lock. They expected that a worthy lock-picking tool would be able to pick the lock without the necessity of additional fixed apparatus that would be easily detected in a real world scenario.

Bramah deemed this challenge to have no practical purpose whatsoever; they were not informed about the method used to open the lock, or given any instrument that opened the lock [it is documented that Hobbs did formally produce several of his lock-picking instruments to the committee, however I wonder if Bramah were only willing to accept one single all-encompassing lock-picking tool? If this was their intention, this point could be fairly argued if we refer to the original challenge signage that Hobbs had initially responded to… “The artist who can make AN instrument …”] There was no information that Bramah could take away with them to help improve their locks – the apparent sole purpose of the original challenge.

With the 30 day period having expired, Bramah dismantled the Challenge Lock and noticed that although there was no concerning damage to the internal mechanism, some of the sliders had been significantly bent then re-straightened, with some others having been almost filed through.

In the 10th September 1851 edition of the Morning Chronicle newspaper, Bramah made the announcement that they had forwarded a cheque to the committee for the 200 Guineas, to be given [whether in good grace or not – the latter, I suspect] to Alfred Charles Hobbs as his reward for opening the Challenge Lock. This cheque was however accompanied by a letter outlining Bramah’s dissatisfaction and protest, also published in this same newspaper article as follows:

“We need scarcely repeat that the decision at which the arbitrators have arrived has surprised us much. We owe it to ourselves and the public to protest against it, and we do so for the following reasons: –

1. Because the arbitrators having been appointed to see ‘fair play,’ and that the lock was fairly operated upon, did not, although repeatedly requested in writing to do so, once inspect [an asterisk in the original text was inserted here with the following footnote: “Mr. Hobbs stated he preferred no one being present, as it made him nervous. If the operation was so delicate – what chance would a burglar have?” – Messrs. Bramah] or allow any one to witness Mr. Hobbs’ operations during the sixteen days he had the sole custody of the lock and was engaged in the work.

2. Because that arbitrators did not once exercise their right of using the key, although repeatedly requested in writing to do so, till after Mr. Hobbs had completed his operations, and then, instead of applying it at once, to prove no damage had been done to the lock, allowed him twenty-four hours to repair any that might have occurred.

3. Because the lock being opened by means of a fixed apparatus screwed to the woodwork, in which the lock was enclosed for the purpose of the experiment (which it is obvious could not have been applied to any iron door without discovery), and the addition of three or four other instruments, the sprit of the challenge has evidently not been complied with.

4. Because, from the course adopted, and opportunity of some good scientific results has been taken from us, as neither arbitrators nor any one else saw the whole, or even the most important instruments by which it is said the lock was picked, actually applied in operation, either before or after the lock was presented open to the arbitrators.

5. Because, during the progress of Mr. Hobbs’ operations, and several days before their completion, we called the attention of the arbitrators to what we considered the interpretation of the challenge, begging at the same time that they would apply the key, and appoint some one to be present during the residue of the experiment, feeling that, whatever might be the result in a scientific point of view, the reward could not be awarded. We would add that we think that several points which appear on your minutes should have been mentioned in your award, more especially that Mr. Hobbs, on the 2nd of June [I believe they meant the 2nd July], took a wax impression [an asterisk in the original text was inserted here with the following footnote: ‘This means as far as he could through the keyhole.’ –Messrs. Bramah] of the lock, and had made, as far as he could, instruments therefrom between that date and the commencement of his operations.”

Hobbs, not suffering from shyness or lack of showmanship, converted his 200 Guinea reward into gold sovereigns and, with a policeman standing guard, displayed them in a glass case on the Day & Newell stand at the Great Exhibition. His signage made it quite clear why this money had been rewarded, and this created a major stir amongst the attendees who wanted to see if this unbelievable story was true. His ego was likely even further boosted upon the announcement that the Bank of England were replacing all their Chubb Detector locks for Day & Newell’s Parautropic locks.

Despite Bramah being awarded a prize medal at the Great Exhibition, their reputation had taken a serious dent. They were pushed into a position where they had to defend their lock that had been so publicly exploited. Writing to the editor of the Morning Chronicle on the 10th October 1851, Bramah wrote,

“SIR, – This controversy having excited an unusual degree of public attention for some time past, perhaps you will be good enough to allow us to state in your journal that the lock on which Mr. Hobbs operated had not been taken to pieces for many years, and it was only on examining it (after the award of the committee) that we discovered the startling fact, that in no less than three particulars it is inferior to those we have made for years past. The lock had so long remained in its resting place in our window, that the proposal of Mr. Hobbs somewhat surprised us; after his appearance, however, no alteration could of course be made without our incurring the risk of being charged with preparing a test lock for the occasion. We were, therefore, bound in honour to let the lock remain as Mr. Hobbs found it when he accepted the challenge. No one inspected his operations during the sixteen days he had the sole custody of the lock and was engaged in the work. We are compelled to adventure another 200 guineas in order that we may see the lock operated upon and opened, if it be possible, and thus gain such information as will enable us to use means that would defy even the acknowledged skill of our American friends. We believe the Bramah lock to be impregnable, and we cannot open it ourselves with the knowledge Mr. Hobbs has given us. We have fitted up the same lock with such improvements as we now use, and some trifling change suggested by the recent trial, and restored it with its challenge to our window. [an asterisk in the original text was inserted here with the following footnote: “The lock remained in the window for four months expressly for Mr. Hobbs to make a second trial. He did not make the attempt: it was then only ‘removed to stop the idle applications of men and boys,’ which took up one person’s time to attend to.” – Messrs. Bramah.] We have not done this in a vain boasting spirit – on the contrary, we feel it rather hard that from the way in which the former trial was conducted we are driven to adopt this course – had any one inspected Mr. Hobbs’ operations during that trial it would not have been necessary.”

Maybe it could be argued that the best defence – and indeed advertisement – Bramah could put forth is that … an extremely accomplished locksmith took 51 hours to open a lock that hadn’t had its design updated for 34 years, under unrealistically perfect test conditions, using multiple tools and fixed instrumentation not subjected to the possibility of detection. This is surely a great credit to the ingenuity of Bramah and their achievements in lock manufacture.

How on earth did Hobbs beat those probabilities?

[I must pose the above question rhetorically, as I am simply at a loss to explain it … but here’s the official story] Behind closed doors there was no magic and no showmanship; Hobbs employed that same exhaustive and methodical process that had previously exposed the insecurity of Bramah’s pre-1817 locks. His process, as quoted from ‘Rudimentary Treatise on the Construction of Door Locks for Commercial and Domestic Purposes’ edited by Charles Tomlinson, reads as follows,

“The first point to be attained was to free the sliders from the pressure of the spiral spring; the spring was very powerful, pressing with a force of between thirty and forty pounds; and until this was counteracted, the sliders could not be readily moved in their grooves. A thin steel rod, drilled at one end, and having two long projecting teeth, was introduced into the keyhole and pressed against the circular disc between the heads of the sliders; the disc and spring were pressed as far as they would go. In order to retain them in this position, a curved stanchion was screwed into the side of the boards surrounding the lock, and the end brought to press upon the steel rod, a thumb-screw passing through the drilled portion of the instrument and keeping it in its place. The sliders being thus freed from the action of the spring, operations commenced for ascertaining their proper relative positions. A plain steel needle, with a moderately fine point, was used for pushing in the sliders; while another, with a small hook at the end, something like a crochet-needle, was used for drawing them back when pushed too far. By gently feeling along the edge of the slider the notch was found and adjusted, and its exact position was then accurately measured by means of a thin and narrow plate of brass, the measurements being recorded on the brass for future reference. The operator was thus enabled by this record to commence each morning’s work at the point where he left off on the previous day. The lock having eighteen sliders, the process of finding the exact position of the notch in each was necessarily slow. Mr. Hobbs employed a small bent instrument to perform the part of the small lever or bit of the key; with this he kept constantly pressing on the cylinder which moved the bolt. He thus knew that if ever he got the slide-notches into the right place, the cylinder would rotate and the lock open. He could feel the varying resistance to which the sliders were subjected by this tendency of the cylinder to rotate; and he adjusted them one by one until the notch came opposite the steel plate. The false notches added, of course, much to his difficulty; for when he had partially rotated the cylinder by means of the false notches, he had to begin again to find out the true ones.”

Price On Application

Price On Application